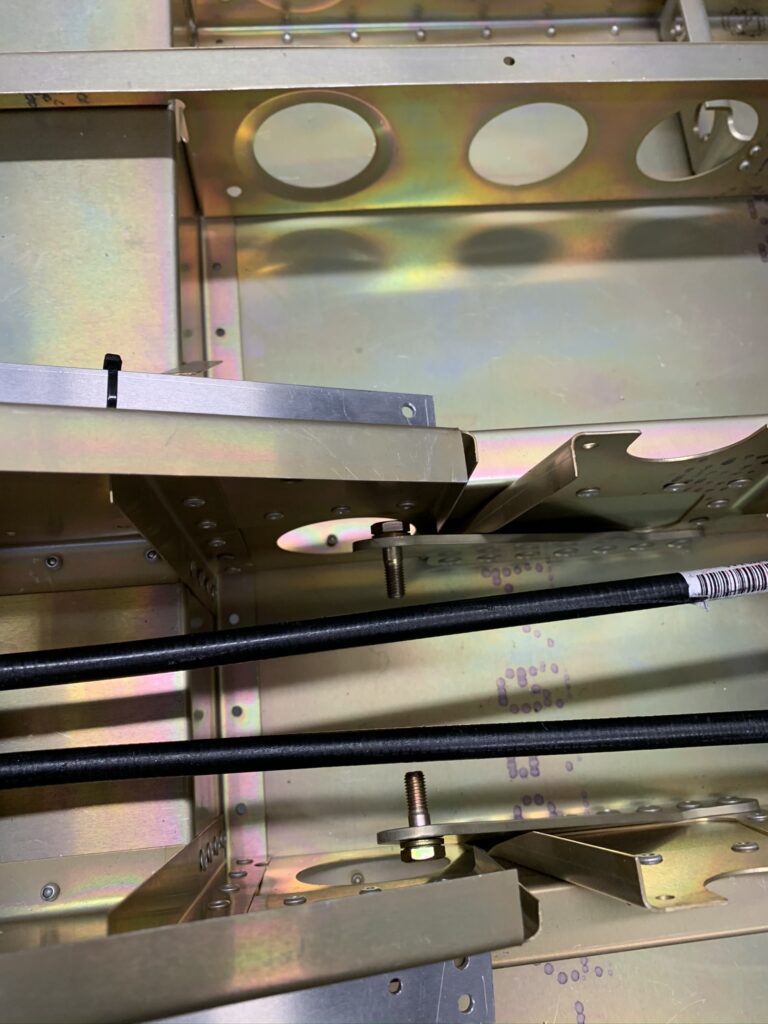

Any work on and in the center fuselage is part of a big step forward. In this case, the work is actually rework, owing to one of several shortcomings introduced during the factory quick-build of my fuselage – which evidently was a bit hasty. TAF admittedly rushed to ship in the last hours before a three week holiday shutdown. Let’s just say there were a few shortcuts taken.

There was a general class of shortcut that I’ve found several examples of – riveting places and parts that shouldn’t have been until other steps were completed. The most vexing examples were the seatbelt anchor brackets being mounted without the AN5-5A bolts and washers in place. I’d noticed this very early on after delivery and have been troubled ever since about how I’d be able to get things as they should be.

As I mentioned in my last post, I finally overcame a mindset that I’d have to drill out and re-rivet the center brackets to place the bolts. With courage and great care I was able to flex my way to a happy result. The outer brackets demanded the drill and re-rivet approach. That has proved very doable, especially since I’ve got the fuselage solidly down on the floor where I can work on it without concern about toppling. Yay again!

I’ve gained some valuable experience with drilling out the big 4,8mm rivets from my rework of the aileron and flap hinge bracket sub-assemblies. With a #12 bit in my lithium battery-powered drill I was able to get the outer brackets off cleanly. And when the time comes, I’ll be able to rivet them back on – with the bolts in place. Glad I don’t have to worry about this anymore.